Since the launch of sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo, platforms that let people crowdfund cash have exploded in popularity. Some companies have even begun offering peer-to-peer lending options for refinancing student loans or investing in real estate.

Professors and students across the College of Business have been studying the changing economic landscape to better position themselves as entrepreneurs and educators.

We talked with four Colorado State University graduates and two business educators to share their best approaches for creating successful crowdfunding campaigns and to see where the industry is headed next.

monkii bars 2

College of Business Global Social & Sustainable Enterprise MBA graduate, David Hunt, led the company he co-founded to a successful Kickstarter campaign that raised over $1 million to create monkii bars 2, a portable suspension training kit.

Co-founder and CEO, The Wild Gym Company/monkii bars

David Hunt’s first Kickstarter crowdfunding campaign only had nine followers and didn’t even hit a quarter of its goal. But less than five years later, the College of Business Global Social and Sustainable Enterprise MBA graduate’s newest project, monkii bars 2, broke the $1,000,000 mark in 42 days, launching the exercise company he co-founded into high gear.

After Hunt’s company eclipsed $50,000 in an hour, he had a simple reflection on the experience.

“It’s a great time to be an entrepreneur.”

As a student in an entrepreneurial graduate program, he was surrounded by faculty and classmates who supported his business-oriented mindset.

“So on a day to day basis I’m looking around the world, kind of noticing problems,” said Hunt, “And thinking, ‘Okay, how could I solve that with a business or a product.’”

What Hunt and his co-founder, Dan Vinson, settled on was addressing the poor-quality outdoor gym equipment. Through developing a solution they came to monkii bars, a portable suspension training kit that can be used over tree limbs, doors, and even off the side of a hot air balloon.

Meraki Printing

Chelsea Williams co-founded Meraki Printing after graduating from the College of Business and raised over four-times her original Kickstarter funding goal, collecting over $140,000 to bring the company’s 2017 Make Sh*t Happen Planner to life.

Co-Creator and Founder at Meraki Printing

In the midst of a Kickstarter campaign for her company’s 2017 Make Sh*t Happen Planner that more than quadrupled its $25,000 funding goal, Chelsea Williams shared some crowdfunding tips and reflected on how the College of Business helped her get an edge in the field.

What’s the most important part of a successful Kickstarter?

“Create a powerful video to showcase your product and tell viewers about yourself. Spend the extra money up front to hire someone to help you make your video as professional as possible.

“Your personal story is an integral part of your product’s story. I’ve found that crowdfunders want to believe not only in the product, but support the mission of the creators as well.

“What is your personal ‘why’ for creating your product? Share that! Be authentic. People love knowing they have helped bring someone’s dream to life.”

Living Ink

After going through the College of Business’s Venture Accelerator program, CSU microbiology alums Steve Albers and Scott Fulbright launched their company Living Ink through a $60,000 Kickstarter campaign.

I am text block. Click edit button to change this text. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Co-founder of Living Ink

As a CSU molecular geneticist working to engineer cyanobacteria, Steve Albers knows how to make algae grow. But when he and a fellow classmate got together to launch a company and sell the world’s first biodegradable time-lapse ink, they weren’t exactly sure how to make the business bloom.

Enter the Venture Accelerator program in the College of Business’s Institute for Entrepreneurship, which provides advising and mentoring to CSU students working to bring their ideas to life.

“I made it explicit that one of our goals was we wanted to start a company,” said Albers. “We were going to learn by doing.”

But succeed or fail, he wanted to come away with the knowledge of how to create a startup and develop a company.

“Through this process we’ve learned to know what we don’t know, and to try and make connections to fill in those gaps,” said Albers. “The Venture Accelerator program was really valuable to help us open our eyes.”

With round-table sessions that gave the co-founders access to consultants, leaders in finance, product development, and crowdfunding, Albers and Fulbright were able to develop a strategy to jump start their company, Living Ink.

Getting results

“The impact was huge on our company,”Albers said.

The Kickstarter campaign they created ended up raising over $60,000, surging past their original goal of $15,000.

“People, I think, often make the incorrect assumption that you make a lot of money from a Kickstarter campaign that’s going to support your company for a long time,” Albers said.

Benefits besides money

Although it tends to be highlighted most frequently, cash isn’t the only thing that can help grow a business. After successfully funding his company’s Kickstarter campaign, Albers gained insights into a few of the lesser known – but equally valuable – ways entrepreneurs can take advantage of crowdfunding.

1. Gain media exposure

Through their campaign, Albers and Fulbright were able to get coverage from Popular Science, Gizmodo, The Coloradoan, The Denver Channel and other publications.

Boosting their visibility helped draw more customers to their company and created a stronger awareness of their product.

2. Identify unique audiences

One of the things that Albers noticed about people coming to their campaign was how distinct the audiences were.

“We started recognizing there were two very different populations here,” Albers said.

They noticed a number of artists who weren’t regular Kickstarter customers arriving at the company’s page to offer praise without necessarily contributing to the campaign. On the other hand more experienced users who knew how the process operated were coming in and supporting the efforts.

“I think that’s one of the inherent difficulties of trying to run a Kickstarter,” said Albers, comparing the process to pitching to venture capitalists and angel investors, where questions and concerns can be easier to predict.

3. Assess commercial viability

Seeing how wide your campaign spreads, and who becomes interested in your product, can be “unbelievably critical” and provide a great metric on how interested potential customers are. Also, having hundreds of people provide feedback on a Kickstarter campaign can be a huge help in identifying a product’s strengths and weakness.

4. Establish your company’s internal goals

Although the direction of Kickstarter is shifting away from product development and more toward helping finished products come to market, Albers and Fulbright were able to lay out a road map for the company’s growth to potential backers, which helped solidify the founders’ plans for their business.

Change Composites

When Nate Saam didn’t meet his company’s Kickstarter goal of $50,000 he didn’t give up, he changed direction to integrate his life-saving helmet technology into other products to help prevent brain injuries.

Our educators

Grace Hanley Wright

CSU management instructor

When Wright co-founded Ascent, a nonprofit that aims to combat maternal mortality and rare diseases, she and her team used GoFundMe to finance two rounds of market research.

In the classroom, Wright has incorporated crowdfunding principles into her entrepreneurship and sustainable venturing courses, teaching students not just from a book, but from personal experience.

1. Plan ahead

Many budding entrepreneurs don’t realize the amount of work that goes into building a Kickstarter campaign, from promotion to developing a realistic financial goal and creating a product or service that’ll catch people’s attention.

“Things don’t just happen, you need a strategy for how your crowdfunding page is going to get from one person to the next, to the next, and then to the 10,000th person from there.”

2. Tell a story

Without a strong story about what you’re hoping to deliver, and why you’re trying to deliver it, an audience may have trouble connecting with your campaign.

Leveraging the social benefit of entrepreneurial projects, like creating jobs or services that haven’t previously been available to a community, can provide an edge in a crowded marketplace – and help people!

3. Remember the fundamentals

“You have to think about your value proposition,” said Wright.

It’s not enough to be all style and no substance. What’s being offered has to meet a need for backers, whether it’s understanding how a charitable donation will support a community or why a product will benefit someone’s life.

“Just like any good elevator pitch, you have to really clearly state the problem you’re trying to solve… and make them buy into your solution.”

Vickie Bajtelsmit

Finance/real estate professor in the College of Business

Vickie Bajtelsmit has taught in the College of Business for 25 years, covering everything from financial planning, investments, corporate and entrepreneurial finance to insurance, and risk management.

Bajtelsmit keeps tabs on the shifting landscape of crowdfunding, sharing her insights with graduate and undergraduate students in her classes.

One of the more common problems Bajtelsmit sees entrepreneurs face is underestimating the capital they’ll need to start their business and support themselves while getting it off the ground.

“I try to help them figure out how much money they need,” said Bajtelsmit, recalling her standard inquiry to those who might not have thought everything through: “Really, you’re going to work for free for six months?”

But with greater access comes a greater need to understand what is driving the growth, how to approach crowdfunding with practical expectations, and things to be careful of.

Background to the boom

There are two main types of crowdfunding:

Donations crowdfunding

Includes charity and rewards based approaches like Kickstarter and Indiegogo.

Investment crowdfunding

Encompasses debt crowdfunding, aka. peer-to-peer lending, where groups of people or businesses loan money to other individuals and companies, and equity crowdfunding, where investors can buy ownership in a company.

One of the most substantial industry changes came about following the 2012 passage of the JOBS Act, which created new funding opportunities by enabling businesses and entrepreneurs to solicit crowdfunded money in exchange for shares of ownership in their companies instead of offering goods or services.

The legislation has enabled startups to publicly advertise their investment campaigns and solicit funds from accredited investors, which they hadn’t been able to do in the same capacity with angel investors and venture capitalists.

However, Bajtelsmit sees pluses and minuses to the shift. There are of course more opportunities for entrepreneurs, but the easy capital allows ideas that might not be fully fleshed out to be fully funded.

Often times venture capitalists and angel investors push entrepreneurs for more details and long term strategies, screening some of the hype that can help crowdfunders become successful.

Or put more simply: “Crowdfunding lets bad ideas get funded too,” Bajtelsmit said.

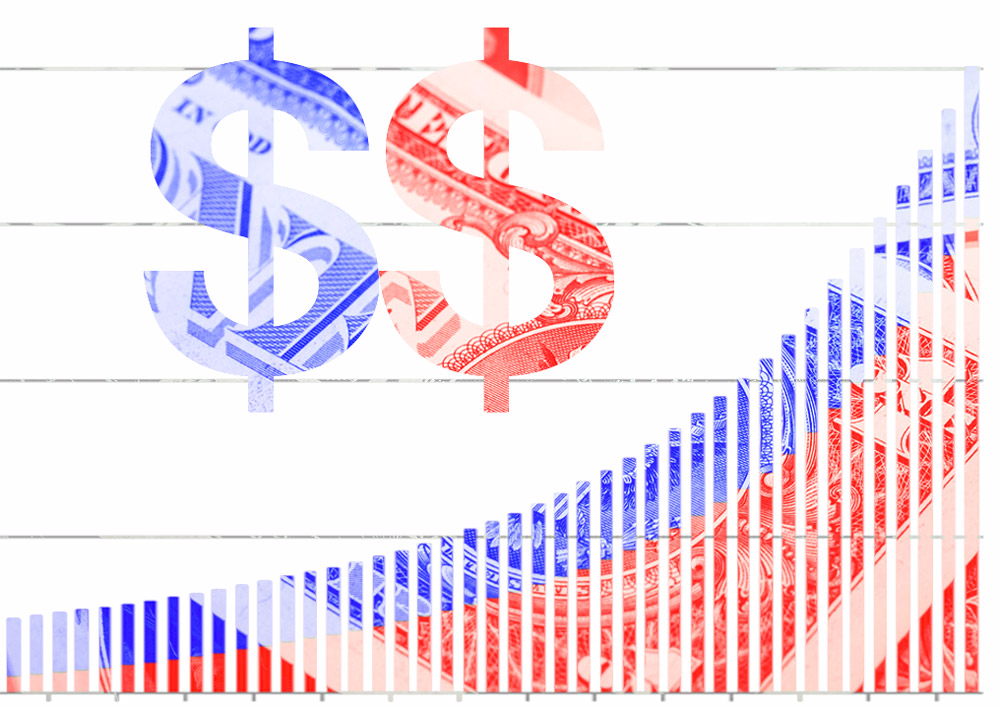

But according to recent research from the University of Cambridge, the crowdfunding market segment with the most growth isn’t helmed by Kickstarter projects, but rather by debt crowdfunding, which in 2015 reached a total of $25 billion in the U.S., dwarfing the $658 million raised by donations crowdfunding.

By removing banks from the equation, debt crowdfunding’s mission was to cut out the middlemen and blend altruistic lending – aimed at people who had trouble finding financing – with low interest rates and high yields for investors.

Yet challenges for backers have cropped up.

“Peer-to-peer lending is a good example,” said Bajtelsmit. “You have no right of recourse, and there are many other legal protections you may be missing.”

However, as the industry and competition have grown, the makeup of lenders has changed. Individuals and businesses are being eclipsed by hedge funds, banks and institutional investors looking to add blocks of crowdfunded loans to their portfolios.

The majority of the debt crowdfunding’s borrowers are refinancing credit card debt, and both charge-off rates and debt to income ratios at the world’s largest online peer-to-peer lender, LendingClub, have risen substantially in the past few years.

Some analysts are worried that the rapid expansion of available credit could lead to an economic collapse similar to the subprime mortgage crisis that kicked off the recession in 2007. As debt crowdfunding sites work to penetrate the mortgage market – which makes up the lion’s share of $8.6 trillion in American housing debt – and peer-to-peer lenders begin to chase the $1.2 trillion student debt market, questions have arisen about what would happen to default rates if the economic climate took a downturn.

Even amid challenges, Bajtelsmit sees the overall growth in access to capital as a good thing.

“I actually do believe we can let people be somewhat responsible for their own decisions, but we should protect people who are at risk of being taken advantage of.”